Introduction

Introduction

This is a written version of a pre-Christmas talk I gave at work recently, about the intersection between Christianity and hacker culture. There’s also a video available here — the sound quality’s not brilliant, but feel free to watch it there!

So who am I, and why do I think I can speak on this topic?

Well, I’m a Christian first. The label “Christian” means different things to different people, but I mean something pretty objective by it — I mean someone who believes the Bible, and specifically believes in Jesus Christ as a historical figure who was born, died, and rose from the dead, to save the world, and to save you and me from our brokenness.

But I’m also a hacker. As most of you know, the term “hacker” has two different meanings: the one you see in the news, which is someone who’s done something illegal using a computer — cracked a military code, or broken into an online bank. But that’s really a “cracker”.

The true meaning of the word “hacker” is someone who loves computer programming, who cares about details, and who likes writing code or solving problems in clever and playful ways. This meaning originates back to the 1960’s at MIT, one of the great engineering schools over in the Eastern United States. It started out as a kind of cross between computer programming and practical joking.

For example, one of the great “hacks” some folks did was assembling a full-size model of a fire truck on top of MIT’s Great Dome. The dome usually looks like this:

But on the morning of September 11, 2006 (kind of as a nod to the firefighters who helped out in the September 11 attacks) the top of the dome looked like this:

But on the morning of September 11, 2006 (kind of as a nod to the firefighters who helped out in the September 11 attacks) the top of the dome looked like this:

They’d carefully built the parts for the fire truck beforehand, and then snuck them up during the night and assembled it on top of the dome. As you can see, they paid attention to detail — there are pressure gauges and a fire hose, and even two “fire dogs” standing on the side of the truck. So you can see the playful and creative side of hacker culture.

They’d carefully built the parts for the fire truck beforehand, and then snuck them up during the night and assembled it on top of the dome. As you can see, they paid attention to detail — there are pressure gauges and a fire hose, and even two “fire dogs” standing on the side of the truck. So you can see the playful and creative side of hacker culture.

But this also comes out in code — in playful or creative solutions to programming problems. If someone writes a spelling checker in 10,000 lines of code, that’s just run-of-the-mill programming. But when someone like Peter Norvig writes a spelling corrector in a handful of lines of quite readable code, makes it freely available, and writes a short article describing how it works, that’s what I call a great hack:

import re, collections

def words(text): return re.findall('[a-z]+', text.lower())

def train(features):

model = collections.defaultdict(lambda: 1)

for f in features:

model[f] += 1

return model

NWORDS = train(words(file('big.txt').read()))

alphabet = 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

def edits1(word):

splits = [(word[:i], word[i:]) for i in range(len(word) + 1)]

deletes = [a + b[1:] for a, b in splits if b]

transposes = [a + b[1] + b[0] + b[2:] for a, b in splits if len(b)>1]

replaces = [a + c + b[1:] for a, b in splits for c in alphabet if b]

inserts = [a + c + b for a, b in splits for c in alphabet]

return set(deletes + transposes + replaces + inserts)

def known_edits2(word):

return set(e2 for e1 in edits1(word) for e2 in edits1(e1) if e2 in NWORDS)

def known(words): return set(w for w in words if w in NWORDS)

def correct(word):

candidates = known([word]) or known(edits1(word)) or known_edits2(word) or [word]

return max(candidates, key=NWORDS.get)

Another aspect of hacker culture is bending the rules. True hackers aren’t into doing things that are illegal or immoral, but we really hate red tape, and sometimes that comes at the cost of stretching the rules almost to their breaking point, but no more. For example, a hacker might hate wearing bicycle helmets. But it’s the law (at least in New Zealand), and you don’t want to get pulled over by a cop. So what do you do? Hack the system — ride a unicycle! Or design a self-balancing unicycle that goes as fast as a bike. There’s nothing in New Zealand law that says you have to wear a helmet on a unicycle … problem solved.

Okay, so what about my own hacker credentials? Well, I’m a computer programmer by day, so really I get paid for hacking. I’ve also written or contributed to several small open source libraries:

- scandir, a better directory iterator and faster os.walk() for Python that I hope to get included in the Python 3.5 standard library.

- Symplate, a very simple and fast Python templating language.

- inih, a tiny INI file parser written in C.

- fabricate, a simple build tool that automatically finds dependencies.

- Third, a small Forth compiler I wrote in 8086 assembler when I was 16.

Anyway, enough intro, and enough about hacking. I think you’ve got the idea. So what about the intersection between Christianity and hacker culture?

Cross-pollination

One of my aims is to give new meaning to the phrase “tech evangelist”. Usually a tech evangelist is someone who wants to promote their technology. My twist on the phrase is that I’m into both tech and evangelism, and exploring how they can cross-pollinate each other. Even the phrase cross-pollinate has a deeper meaning.

At first glance, hacker culture seems predominately agnostic and atheist, but an interesting fact is how many well-known hackers and computer scientists believe in God. Four of the more well-known ones are:

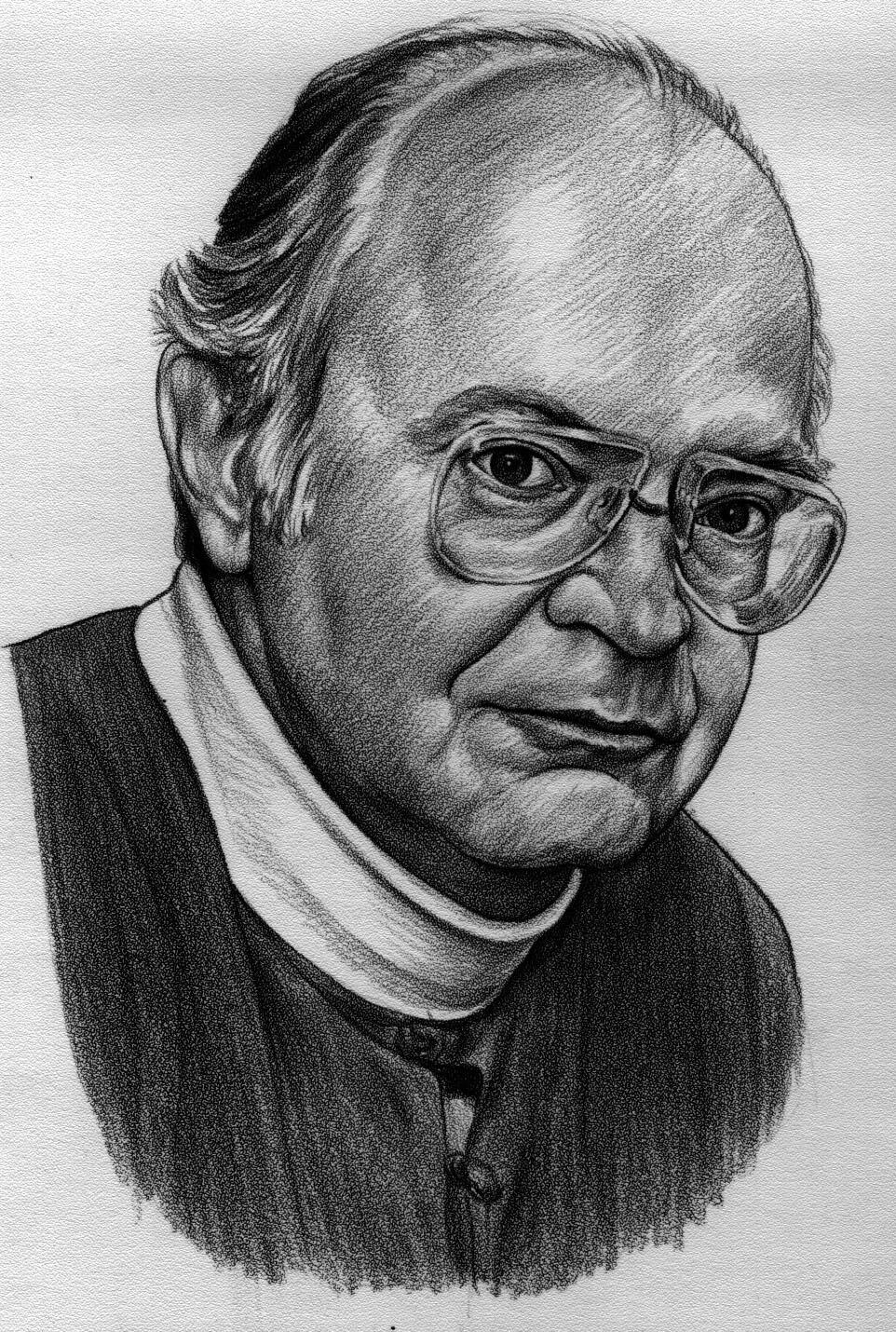

- Donald Knuth is basically the world’s most-respected computer scientist. He wrote the multi-volume The Art of Computer Programming and the TeX typesetting system. He’s also written some stuff that directly combines computer science and Christianity, such as the book 3:16. He’s 75 now, and kind of my personal hero — I even told my wife all about how cool he was on our honeymoon.

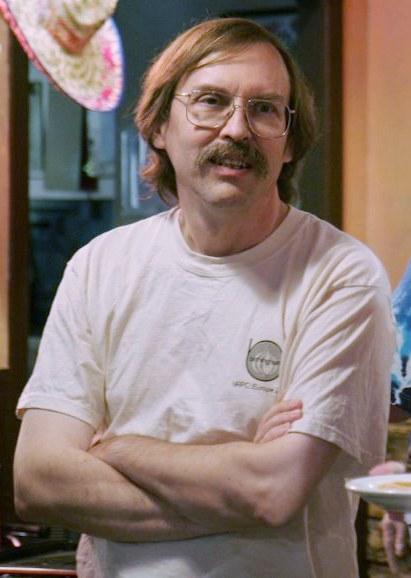

- Larry Wall, the creator of the Perl programming language, which is said to be the duct tape that holds the Internet together. He says he kind of considers himself “an apostle to the hackers”.

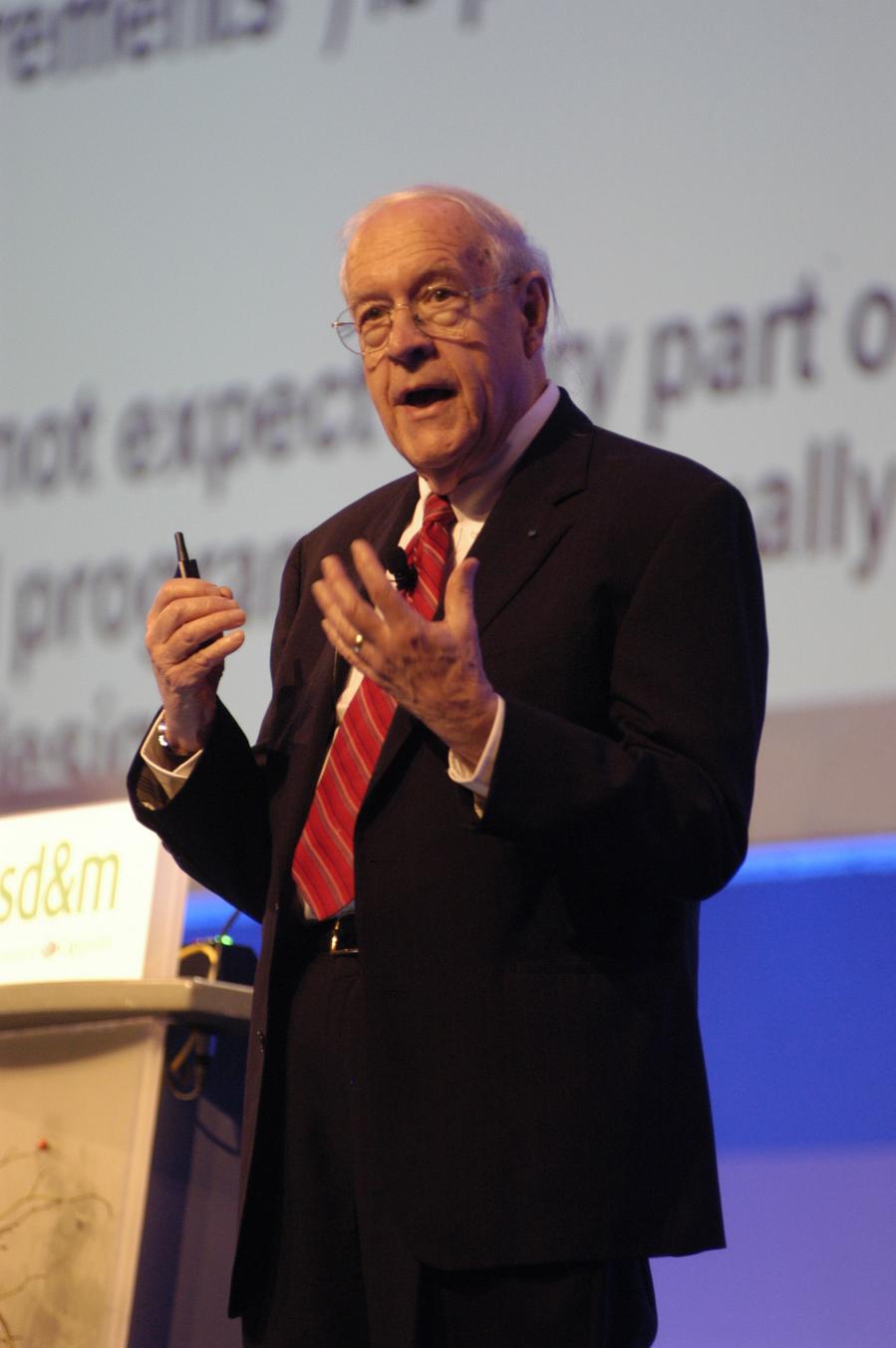

- Fred Brooks, who wrote the classic book about software engineering, The Mythical Man-Month.

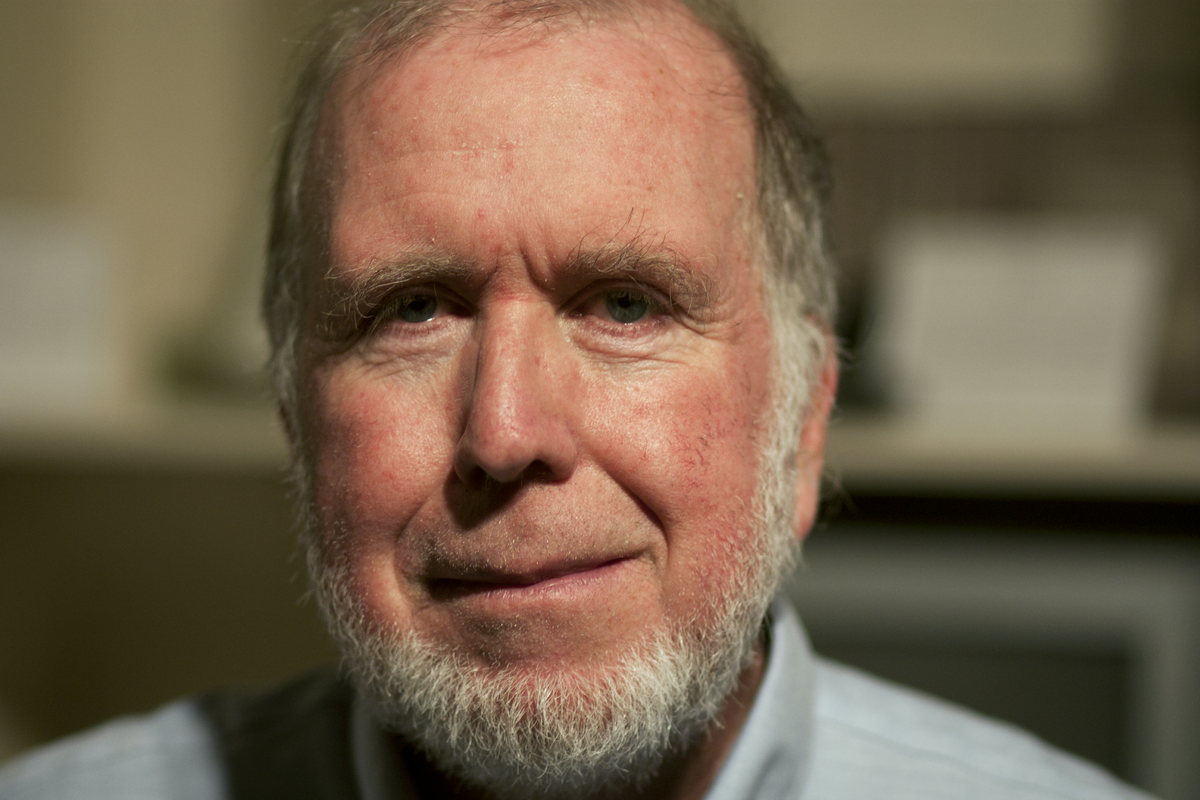

- Kevin Kelly, founder of Wired magazine, is a devout Christian and also a “futurist” (not a combination you see every day). Keanu Reeves was required to read one of Kelly’s books before playing Neo in The Matrix movie.

Each of those people is incredibly interesting in his own right, whether you’re more into the hacker side of things or the Christianity side of things — go check them out.

In terms of how the two cultures can influence each other, first up, I think Christians can learn a few things from the hacker community about contributing to “open culture”. In the programming world you’ve got open source software, where people share the source code for their programs freely. Linux, Firefox, Android, the Apache web server … these really have made the computing world a better place. Budding hackers can learn from code written by top programmers, because they’ve made it freely available to use and modify.

In the Christian world, there are some free things, such as sermons, articles, and the King James Bible — that’s in the public domain, but only because it’s so old. Newer Bible translations are all proprietary pay-ware, like Microsoft Word. Various hackers have come up with free software licenses like the GPL, and free culture licenses like the Creative Commons licenses. And they’re starting to influence Christians. A notable free Bible is the Open English Bible, which is developed on GitHub. There’s also the NET Bible and the English Standard Version, which are at least free as in beer.

Then there’s the “commercial Christian music scene”, which is a can of worms I’m not even going to open tonight. But I will quote Larry Wall’s quip on how researchers and artists can have the best of both worlds — get paid for their work as well as give their creations away for free. When he worked at O’Reilly, Larry Wall said, “Essentially, my position is what you call a patronage. It’s a very old-fashioned idea which goes back to the time when there was an aristocracy and they would support artists and musicians. They would have a patron, Tim O’Reilly is my patron. He pays me to create things, to kind of be in charge of the Perl culture.”

A little aside about Creative Commons. This is really great. You write something, you copyright it as Creative Commons, and there are some different options you can choose, but basically you’re giving people the right to use it totally free of charge, and mostly free of restrictions. Creative Commons is actually straight from the Bible — it’s just phrased a bit differently: “Freely you have received; freely give.”

So I think Christians could learn a thing or two about open culture from the free software movement.

Speaking of free software, Richard Stallman, who founded the Free Software Foundation, is basically an Old Testament prophet for his movement, right down to his massive Moses-like beard. I think he’s a bit of an extremist, but sometimes it takes extremes to get people to listen. Since the 1980’s, he’s basically been telling people — in software terms — to go sell their possessions and give everything to the poor. His message is software freedom: that people who use software should be allowed to study and modify how it works. And just like an Old Testament prophet, he phrases it in very black and white moral terms. Still, despite his extremism, I think the overall effect is good. Many people have been inspired to release their software and source code freely, making the programming world a better place.

But the Free Software Religion isn’t ready to take over the world quite yet. And a couple of years ago, I discovered why — their music kinda sucks. Just for fun, if you click the play button below you can subject yourself to two minutes of Richard Stallman singing the Foundation’s “free software song”. Apologies in advance for any cerebral damage caused:

Admittedly Christians have had 2000 years longer to develop good music, but that kinda makes me feel sorry for the Free Software Foundation. I grew up on classical music and solid church music, for example:

So yeah, if you’re a musician, join the Free Software Foundation — they seem to need your help.

Another point of cross-pollination that I’ve written about before is the Reformation — back in the 1500’s when Protestants split from the Catholic Church. I think the Reformation was an incredibly interesting time in history. It’s like Eric Raymond’s essay on open source, The Cathedral and the Bazaar. The Reformation happened when the cathedral model had reached a breaking point; what the world needed was a bazaar.

The Church had effectively made the Bible proprietary software. It was in Latin and very few people could read it; in fact, you weren’t allowed to unless you were a priest. Then along came Martin Luther and established the Free Scripture Foundation. Shortly afterwards, John Calvin and John Knox made the whole thing open source. Johannes Gutenburg founded GutenHub.com to help distribute all of this good stuff.

So that’s some of what hacker culture can offer Christianity, what about the reverse? Does Christianity have anything to offer hacker culture? I believe it does. Hackers do some really good things, but I think they suffer from lack of moral foundation. Put another way, we hackers are nice people, but we can’t explain why.

That’s really where Jesus comes in. He made the world a better place not just by giving a few hours of his spare time; he gave his life. So there’s this concept of sacrifice at the center of the Christian view of things that shapes everything else.

But isn’t Christianity about rules? Actually, it’s not. It’s about crash recovery for programs that have already broken the rules and crashed the system. Of course, there are commandments, but there are only ten — everything else is allowed. The Ten Commandments represent a very positive moral outlook, but they’re stated negatively because they’re like boolean logic. It’s much shorter to say “thou shalt not” do this one thing than to list all the hundreds of things you should be doing:

# Which "commandment" would you prefer to maintain?

# This:

if action != 'murder':

perform(action)

# Or this?

if (action == 'helping_save_a_life' or

action == 'going_to_the_doctor' or

action == 'random_act_of_kindness' or

action == 'helping_old_ladies_across_street' or

action == 'teaching_kids_how_to_code' or

action.startswith('good') or

action in other_good_deeds):

perform(action)

It’s also much less restrictive, because there’s only one thing you can’t do, rather than hundreds you have to constantly remember to do. As one example, it’s simpler to say “thou shalt not commit adultery” than to say “make sure you always respect your wife, be faithful to her in bed and out of it, buy her flowers, learn her love languages, etc etc”. And programmers love brevity — why use 50 words where 5 would do?

So I think programmers could do a lot more good if we had a clearly defined moral foundation. For example, we know it’s wrong to discriminate against women in tech, but when someone does it, all we can say is “bad programmer” (or maybe “bad brogrammer”). Why is it okay to degrade women while playing Grand Theft Auto, but morally wrong at a tech conference? I humbly suggest that hackers would do well to take a page out of The Good Book on some of these issues.

What if we truly believed “do unto others as you would have them do unto you?” In fact, in this specific case of showing respect for women, Jesus actually got the ball rolling — the very first people he appeared to after he rose from the dead were women. This was a subversive cultural act — a “hack”, if you like — because in those days women didn’t get much air time.

The ultimate hack

The Christian story is full of hacks — sometimes elegant and beautiful hacks, at other times downright hackish hacks. It begins in the book of Genesis with a beautiful hack — God simply spoke, and the universe appeared. That’s voice-activated 3D printing on a cosmic scale. Trees and animals and men and women were also created by God speaking.

Then there was the Fall. We (the programs) decided we didn’t like the programmer’s logic. We ate the forbidden fruit. We asked for it — and we got the first core dump; the first blue screen of death.

That begs the question of why God allows evil? There’s a very simple hacker’s answer to that: He didn’t want us living in a sandboxed environment. In the programming world, you can create safe places for code to run, called “sandboxes”, where the code can’t do anything bad to the system. In a web browser, this is a great thing — imagine if you visited a web page and it deleted all the files off your hard disk. But then imagine if your operating system was in a sandboxed environment. Basically nothing useful would be allowed, and nothing could happen. You could never do factory automation or smart traffic lights.

We don’t have to log in to Life every morning as a user with restricted access. Instead, God gave us freedom to break the rules, and ultimately to crash the system. It’s like writing low-level C code for the Linux kernel. It’s very unsafe, but very fast and powerful. However, the next thing God did was to start implementing His crash recovery program.

Along the way, He continues to use various hacks to achieve His goals. He chooses to start with Israel, a tiny little nothing kind of country, when He could have chosen one of the world super-powers: Egypt, or Persia, or Greece, or Rome. He picks a woman named Rahab, who was a foreign prostitute, to be part of the royal bloodline. He chooses David to be a king of Israel and ancestor of Jesus — David, who was half the size of his handsome brothers and only a simple shepherd. The least shall be the greatest.

Then Jesus, who’s an instance of God himself, enters His own program as an unprivileged process. He’s like the author who writes himself into his own novel. Even the way Jesus enters is a hack of the human reproductive system — a virgin birth. He tweaks the laws of physics plenty of times with hacks that we still can’t figure out: turns water into wine at a wedding reception; walks on water; raises someone from the dead; miraculously makes people well. Because He’s the Programmer, these are not hard for Him to do.

But the culmination of all this is the ultimate hack. The Romans used crucifixion as a very cruel form of torture to send a loud and clear message that being a traitor was not okay. It was a slow, painful death. The Roman leaders knew Jesus was innocent, but they condemned him to death anyway.

But in an incredible twist, God uses this cruel death to bring life. After three days, Jesus comes back to life, and in doing so, opens a portal to eternal life. It really is the ultimate life hack. In one act, death is reversed. Sins are paid for and forgiven. This one act of self-sacrifice set in motion a thousand others, and Christianity spread like wildfire in the ancient world.

But now to make it a bit more personal: God didn’t put you, or me, in a sandboxed environment either. We don’t play by the rules; we don’t follow His protocol. He lets us stuff up, and in the course of a lifetime we cause enough core dumps to fill a hard drive. That’s the bad news.

But the good news is he didn’t stop there. Christians talk about “Jesus dying for our sins”. But what that means is that He cleaned up our mess for anyone who relies on His solution. He fired up the debugger on each one of our core dumps, found the source of the problem, and fixed it. And He didn’t charge us a thing — it was all free, and it’s all open source, right in the gospels.

This really changes your philosophy; but it also changes the way you act. I’m really thankful that God “debugged my code” free of charge, and the least I can do is follow the protocol and give back to the hacker community. Again, in Christian speak they call that “doing good works”, but it’s the same thing.

So in this sense, God is a hacker — He’s the implementer of the ultimate hack. But there’s also a difference between God and ordinary hackers. God is also described as the ultimate Father. And Fatherhood is not something talked about much in hacker circles.

As a Father, God loves the world, and good earthly fathers love their families. But because God made us, and because we’re so much younger and so much smaller than God, he also requires our respect … He even says to “obey” Him. Now there’s a word you never see in hacker culture.

But once again, there’s a good hacker analogy. Programming languages often have a BDFL (Benevolent Dictator For Life) who’s in charge of the language. The dictator part — are they in charge? Yes, they are, they call the shots for that programming language. Are they good guys, are they actually benevolent? Usually they are. It’s the same with God, except that he’s not a dictator, he’s a King. And he’s not just a “good guy”, he’s the source of all Goodness.

I want to challenge Christians not to ignore the powerful concepts and analogies that hacker culture brings to the table. But I also want to challenge hackers: if Jesus was a historical figure, and if he did actually sacrifice himself and conquer death in the ultimate life hack … isn’t that a patch we should find out about and apply?

So there you have it. That’s the Christmas story, the Christian story, in hacker terms.

Further reading

- God, the Hacker: Technology, Mockery, and the Cross by Martin Olmos — the idea of God being the ultimate hacker isn’t new with me; this is a really interesting article I found while searching for info on the subject.

- Theological Cultural Analysis of the Free Software Movement by Gervase Markham — some great thoughts on the Free Software Movement from a Christian perspective.

- What Would Jesus Hack? — probably the only news article I’ve read that brings together the Vatican, Larry Wall, and Wired magazine. (More from the Vatican here.)

- Geek Theologian — interview with Wired magazine co-founder Kevin Kelly, in which both his futurism and his religious beliefs came out quite clearly.

- The Reason for God — a great book by Tim Keller that asks and answers some of the hard questions about religion from a thoughtful, Christian perspective.

Comments (5)

Thanks for the link to our site. Great post. If you ever wanted to write more about the topic, we’d be very interested in publishing it. Drop us a line if you’re interested!

You’ve made it to Holland. Though being a newbie to programming, it was fun to read.

Now consider the ten commandments as a software license in case you want to run life autonomously (is that a word?) or independent.

Than consider Jezus’ work also as complete fullfilment and payment for eternity for this license.

It sets everything free to use, whilst complying to all regulations and paying off any debt.

Combined with a patched core, the possibillities are unrestricted and endless without our own labor.

Just a thought while stumbling over the language barrier.

Anyway bless you with unlimited powersupply and a stable hardware configuration. ;-P

Hi Ben,

I’m sorry I missed your talk last year at EPIC. It was fun to read through your thoughts.

I’ve quite often wanted to allude to our (collective and individual) relationships with the Almighty in terms of programming metaphors but have been too scared of being cited as a heretic (or just plain silly).

The allusion that appeals most to me comes from Paul’s great discourse in 1 Cor 15, “we shall all be changed…” Try substituting “refactored” for “changed” and ponder for a bit. Dead, “evil”, code removed and replaced with kewl stuff from the hand of the Creator!

I regularly remind other believers that the resurrection is new bodies — yes of course…

But also new hearts (read minds). I used to wonder how I’d last 5 minutes in heaven — without sinning! The answer of course is quite apparent if you read through chap. 15 and elsewhere.

Have a look at the end of verse 54 through 57. Death swallowed up in victory (tick). Sting gone (tick), which is >>> sin <<< (gonebuster!!!).. whoohooo!!!

Oh yeah, I'm the guy who turned up one day at brush to say hello and hand out cards.

Maranatha!

— Steve Simpson

www.leeson.co.nz

Hi, I love the way youve explained christianity using hacker terms.

Do you mind if I make an animation based on it???

I’ll give you full credit, let me know what you think.

Alex — sure, go ahead, be creative! Bonus points of if you write a comment here and link to it when you’re finished. :-)